Content warning: extreme antisemitism, ableism, transphobia, homophobia

Conversations on the Internet can have a frustrating undercurrent; what may start as a simple statement can undergo a transformation in responses so drastic that it no longer vaguely resembles the initial comment at all. Moreover, the Internet is masterful in its spread of misconceptions, shedding the burden of accuracy for the goal of proving a point, no matter how valid the point is.

Discussions surrounding goblins have often taken this course. Nuance is generally given a backseat in conversations to allow dogma to steer a conversation in a particular direction: Goblins are either inherently good or bad, bigoted or innocent, antisemitic or entirely free of resemblance to any caricature--and depending on who you listen to, you are actually the bigot for thinking that goblins in any way resemble antisemitic stereotypes. The Internet wants an easy answer: a yes or a no. But nuance cannot be thrown out for the sake of ease.

To know how these creatures relate to Jews and whether they are potentially antisemitic, we must first explore and understand their complex history.

What is a Goblin?

William A. Senior cites David Pickering's Dictionary of Folklore, which mentions goblins ‘"generally grotesque appearance" and proffers the following curious description: "In European folklore, a mischievous breed of demon that delight in playing malicious tricks upon mortals. Variously depicted as inhabiting houses, mines, or trees, goblins are closely related to dwarfs [sic] and gnomes but are usually regarded as a more malevolent species." ⁶

Various folklorists label goblins differently; however, it is commonly understood in folkloric circles that “[t]he term goblin referred to any of the grotesque, small but friendly brownies- like creatures among the Fay. Later, it also included the sub-terrain species as well as fairies with a hurtful and malicious intent, such as the knocker, kobold, phookas, spriggan, troll, and trow. Goblins date back to the fourteenth century and probably derives from the Anglo-Norman Gobelin, similar to Old French Gobelin.”⁴

The goblins of common mythology are almost entirely of European imagination; the term only later expanded and evolved to further encompass and absorb creatures stemming from mythologies from further around the globe.

“They are nasty little creatures with a human demeanor, but much smaller in size and with horrific, deformed faces. They are closely related to the helpful beings of Celtic myths. They come from the folktales of France. They are believed to have emerged from the Pyrenees Mountains of Southwestern France, the dividing mountain range between France and Spain. After leaving the mountain, they spread throughout France and multiplied over Europe. After infesting Scandinavia, they came to the British Isles. The native Celts of Britain called the invaders as Robin Goblin. The term hobgoblin derives from these invaders. The stories about these creatures spread throughout Europe. The reputation of the goblins became more sinister over the ages. Hobgoblin shortened to the goblin.”⁴

Of vital importance is the fact that there is not one specific creature that has the label:

“The word goblin did not mean any specific type of fairy being. Writers used goblin as a generic term along with the elves and fairies. In the earlier periods, writers used goblins as synonyms for other types of fairies of malicious and evil connotations, such as Thurs and Shuck”⁴

You may not be able to answer the question succinctly when asked, “what is a goblin?” but if you were to describe one, chances are that your answer would align with conceptualizations that solidify reasonably well with the descriptions listed above and in the section entitled descriptions. You know a goblin when you see one, even if you cannot accurately label or categorize them.

The fallacy of terminology

While we’ve just described the common understanding of a goblin today, we are operating under today's knowledge. Humans tend to seek out common words across cultures to unify concepts under single umbrella terms so that they can be easily understood by the masses. This is not always agreed upon by marginalized groups and often comes at the expense of minorities who suddenly find their creatures and concepts exploited under a different name.

Look at vampires today: now, most human creatures who drink blood, usually from the neck, are called vampires, a term that only came to popularity in the 1800s, where previously they would have been known by the names specific to each unique culture. In Jewish communities, for example, they may be known as alukah, broxa, estries, etc. But this doesn’t change the variations we see within each individual mythos, even the modern ones. For example, the modern mythological vampires from Twilight (white, pale skin that glitters in the sunlight, not nocturnal, requires no sleep, impenetrable stone-like skin [cannot be staked or poisoned, only killed by other supernatural creatures, essentially], physically fast and strong, etc.) versus the vampires from Vampire Diaries (can be of any race, can be staked, can be burned by sunlight, can be harmed by humans, harmed by the plant vervain, fast, strong, etc.). Though these are both modern vampires, their lore is more Venn diagram than complete circle. Despite sharing the same name, they are not identical creatures.

Goblins, too, have been subjected to this homogenization: any creature that falls within our modern, extremely wide-reaching definition has been lumped under the umbrella of ‘goblin.’ In later sections of this article, we will examine some of the contributors to the modern goblin archetype.

Fairytales as Propaganda

European goblins existing within various folktales did not spring up out of the blue. Folklore and cultural stories are often rooted in the values, morals, and systems in place in these communities. When the word goblin was created, antisemitism was rife within Europe. Perhaps the most common argument of why goblins as a whole cannot be antisemitic is that “goblins originate in 14th century Europe”. While this is wholly inaccurate, as we’ve already described, let’s look at Europe.

Leading up to the 14th century were the Crusades, during which Jewish communities across Europe were slaughtered en masse. As a result of the Spanish Inquisition, Jews were either forced from Spain or murdered; the only other option was to convert to Catholicism, but even converting did not save you, lest you were suspected of being a converso, or crypto-Jew. There were also centuries of blood libel accusations that resulted in the persecution and murders of Jews in communities across Europe. In 1290, England expelled its entire Jewish population. Jews were often forced to wear clothing that specifically identified them as Jewish so that Christians would not accidentally mingle with filthy Jews. In the 14th century, the Black Plague descended upon Europe, and Jews were often the scapegoat for why such a horrific disease claimed the lives of so many. In Strasbourg in 1349, for example, 2000 Jews were massacred because of this propaganda. Wikipedia labels the years "1096-1349" as "A Period of Massacres" of Jews in Germany. This is all to say that Jews were not commonly met with kindness and understanding in the European mindset. The folklore of many Europeans reflected this deep seeded hatred of Jews.

While this article is explicitly discussing cartoons and visual media of that sort, visual arts and descriptive language have long been used as propaganda: Author Balakirsky Katz wrote on “the embedding of politicized images, including those of ethnic minorities, in the depiction of exotic fairy-tale characters and their magical landscapes”²

Just as we use fables to teach our children morals, fairytales and mythological creatures were used to convey messages across European society. Below is a section on Grimm: many of you probably read or were told Grimm’s fairytales growing up, though this particular tale may not have made it to your bedtime story roster, and for good reason. Its purpose is to indoctrinate you into a hatred of Jews. There is even a section of the Jewish Virtual Library dedicated to antisemitic legends within Europe, featuring twelve tales (though not the one we have highlighted further down).

Below is an image from the book Der Giftpilz, a Nazi-era children’s book that taught children to fear, hate, and detest Jews who could ‘blend in just like a poison mushroom could blend in with normal mushrooms.’ The image on the right depicts young children learning to identify Jews by the shape of their noses.

The text reads, "The Jewish nose is crooked at its tip. It looks like the number six..." Via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Physical Markers

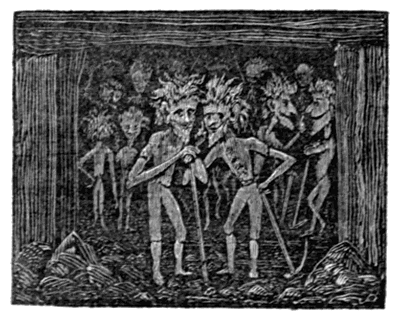

One of the most common forms of dehumanization that Jews faced was the literal and imagined dehumanization in art and media of the times. When looking at both modern and Medieval depictions of goblins, there are striking resemblances to antisemitic caricatures from both periods.

In the imagination of a Medieval European, Jews were imagined as demonic, including horns, tails, an inhuman, Jew-specific stench, huge, crooked and hooked noses, long, clawed fingers, sallow, olive skin, bushy, wild, dark hair, hunched backs, even wings, clawed and cloven hooves, and a generally disgusting appearance. You can read here the highly similar description of the Devil and Jews, down to the scent.

However, there were some exceptions. For example, the Belle Juive: a literary trope that generally imagines Jewish women as evil seductresses who seek out Christian means to entrap or otherwise link her to the Virgin Mary by contrasting her with her ‘evil Jewish brethren’ that she must forsake to come into the light of Christianity.

The similarities between antisemitic imagery and goblin imagery are striking. If you were to mislabel them and remove the apparent identifiers (for example, Stars of David), one might even confuse the two.

Jews were often depicted as animals; referring not only to the "subhuman" nature of Jews, but also to the belief that Jews were capable of magic, such as shapeshifting into inhuman forms.

Grimm

Grimm’s Fairy Tales serve not necessarily to answer the question of “what is a goblin?” but rather to answer the question of “what do fairytales have to do with antisemitism?” The neighboring question of Grimm’s antisemitism is easily answered. Not only did the brothers partake in the ‘creation of German nationalism,’ but they published wildly antisemitic works when said works were not necessary for the preservation of fairytales [e.i choosing the most antisemitic iterations of the folk tales when more benign ones were more common, seemingly in order to spread antisemitism further], aiding in laying the foundations for the rise of Nazism in Germany and the German-speaking world at large. Their works were quickly translated into numerous other languages. One specifically antisemitic tale, though not including goblins, is that of The Jew in the Thorns, which highlights how the Brothers Grimm sought to specifically Other Jews.

“A naïve young man works diligently for little money; when he is finally paid, he goes out into the world and gives his money away to the first beggar he meets. The beggar grants him three wishes: a weapon for shooting birds which never misses, a fiddle that will make everyone hearing it dance uncontrollably, and the ability to have any request he makes impossible to deny. So far, so good: the simple but generous soul is a figure often found in fairy tales, and we expect he will now be rewarded beyond his wildest dreams. But things develop differently, quickly disintegrating into random and unprovoked racist violence. The young man comes across a Jew listening to a bird singing, and generously offers to shoot the bird down for him. When it falls into the thorn bush beneath the tree, the Jew crawls in to get it – and the young man begins to play the fiddle. Only when the Jew is reduced to a bloody state and his clothes are torn to shreds does the young man stop, and then because the Jew offers him all the money he has on him. In the next town, the Jew accuses the young man of highway robbery, a charge that seems reasonable to the officials there, and the young man is condemned to hanging. He asks for a last chance to play his fiddle and makes everyone dance to exhaustion until the judge promises him freedom if only he swill stop. The Jew then unaccountably confesses to having stolen the money, which he says the young man has now ‘earned honourably’ and the Jew is hanged instead.”¹

It is critical to understand that the Brothers Grimm were not only writers of folk tales for enjoyment–they were folklorists, anthropologists, lexicographers, and academics whose works have impacted billions. For example, their works have been remade by Disney and the like. The pervasive nature of Grimm is a solid indicator of how effective folklore is at indoctrination.

Shakespeare

Some argue that one of the originators of the modern goblin was the Bard, who was an unmistakable antisemite. His works were rife with antisemitism, though perhaps no more prolific than the Merchant of Venice.

“According to Ernest A. Rappaport, a survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp and a psychoanalyst who wrote on the blood libel, “Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice is a ritual murder accusation . . . [where we find] the repetition of the drama of the crucifixion with the gentle, self-sacrificing Antonio in the role of Christ and Shylock representing the stereotype of the unscrupulous, cruel Jew.” Brian Pullan points out that in a trial concerning usury that took place in Venice in 1567 and 1568, the charges began with the explicit claim that “the aliens [i.e., Jews] lent out moneys upon usury and sucked or swallowed the blood [italics mine] of everyone who fell into their hands.” Blood drinking, Pullan adds, was a common metaphor for money lending, and, as observed earlier,”³

Gratefully, his works containing overt antisemitism do not include goblins. However, his contributions to the goblin archetype were foundational in a literary sense, debuting his goblin in several plays. His character of Puck, believed to be plucked from A Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginald Scot, published in 1584 (and subsequently ordered to be burned by King James I of England), being most prominent.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck is referred to by one of Titania's fairies as ‘hobgoblin’, while he recites,

“Up and down, up and down,

I will lead them up and down:

I am feared in field and town:

Goblin, lead them up and down.”

His use of the goblin here indicates it to be his identity, the inner core of who he is. For those unfamiliar, Puck is a supernatural, mischievous character who sets about to cause trouble for the other characters. Depending on the production, his characterization often includes horns and pointed ears but can also include prosthetic noses to increase his ‘grotesque’ appearance.

Shakespeare mentions goblins as well, for example, in Act 1 Scene 4 of Hamlet, goblins are seemingly cast in the same lines as demons: the antithesis to health and goodness in damnation, relating them to hell.

Angels and ministers of grace defend us!

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damned,

Bring with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

By thy intents wicked or charitable,

Though comest in such questionable shape

That I will speak to thee.

Though we will not interrogate his works, Milton’s Paradise Lost also refers to goblins when approaching the guardian at the gates of hell.⁶

Tolkien

Tolkien’s goblins, ironically, do not correlate directly to Jews, but we would be remiss to ignore one of the most significant contributors of the codifiers of modern goblin lore. Tolkien perhaps did not intentionally draw inspiration for his goblins from Jews. Instead, he is quoted as putting Jews into his works as dwarves, embodying antisemitism in other ways, though it would appear not intentionally.

"I do think of the 'Dwarves' like Jews: at once native and alien in their habitations" and "[t]he Dwarves of course are quite obviously —couldn't you say that in many ways the remind you of the Jews? Their words are Semitic, obviously, constructed to be Semitic [...]" ⁵

“There is it: dwarves are not heroes but calculating folk with a great idea of the value of money; some are tricky and treacherous and pretty bad lots; some are not, but are decent enough people like Thorin and Company, if you don't expect too much. ⁵”

Even the written origin story of the dwarves themselves is steeped in antisemitism: “The Dwarves are (briefly) the first race awakened in Middle-earth, but they are not the chosen people, the Children of Iluvatar.”¹⁰ They are replaced by the next races, living out a replication of Christian supersessionism which sees itself as the replacers of the covenant “Christianity was a new religion that had replaced Judaism and that the Christians were now God's chosen people instead of the Jews. In this context, the origin of the Dwarves as the first-awakened race but not the chosen people is a striking similarity.”¹⁰

Tolkien’s seeming anti-Nazi beliefs were documented: he apparently praised Jews, abhorred race science, and his letters to publishers asking if he were of Aryan descent are available to the public to read. But as many scholars of antisemitism will preach: you do not have to have a conscious hatred of Jews to hold antisemitism within you.

Tolkien was born and raised in a mire of antisemitism; it was the water of the womb and the blood of the covenant; to forget the ideology that is baked into your very upbringing must be an intentional act, and scholars have theorized that he realized his latent antisemitism and made retractions and changes to his work to reduce the impact of his unconscious antisemitism: “Tolkien’s revisions, Brackmann suggests, “might have had a tinge of guilt under it, as he realized that the tying together of unpleasant stereotypes about Jews in his depiction of the Dwarves drew on beliefs that could have horrifying consequences for the real people so perceived.”⁹ But this latent antisemitism very well may have informed his creation of his goblins.

In The Hobbit, readers are introduced to goblins, creatures described as “big, ugly creatures, "cruel, wicked, and bad-hearted."¹¹

In The Lord of the Rings, however, goblins are rarely mentioned; rather, the same creatures are referred to as ‘orcs.’ Tolkien himself gives the explanation that “Orc is not an English word. It occurs in one or two places [in The Hobbit] but is usually translated goblin (or hobgoblin for the larger kinds).”¹¹ However, Tom Shippey, one of the foremost scholars on Tolkien, notes that Tolkien “preferred an Old English word [referencing orc], and found it in two compounds, the plural form orc-neas found in Beowulf, where it seems to mean 'demon-corpses,' and the singular orcpyrs... [which] means something like 'giant'”.⁶

The depictions of Tolkien’s goblins, however,fall in the middle ground of demon-corpse descriptions, as described by the etymological root of orc and the inspiration for Tolkien’s goblins: The Princess and the Goblin.

Tolkien acknowledged that he was inspired by the children’s book originally published in the late 1800s and included black and white illustrations, which would evolve with new editions.

Dungeons and Dragons

Unlike some other sections here, the Dungeons and Dragons franchise has seen many different authors and contributors. Dungeons and Dragons were undoubtedly inspired by Tolkien, unabashedly using his trailblazing ‘creation’ of the goblin/orc combination, though, in DnD, goblins and orcs hold different classifications.

According to DnDBeyond, “Goblins are small, black-hearted humanoids that lair in despoiled dungeons and other dismal settings. Individually weak, they gather in large numbers to torment other creatures.”¹⁴ Goblins live in ‘tribes’ and “enter civilized areas to raid for food, livestock, tools, weapons, and supplies.”¹⁵ They have a number of subspecies.

The goblins are considered ‘neutral-evil’¹⁴, and in many campaign settings, the main pantheon worshiped by goblins include “Maglubiyet, the god of war and rulership,...the chief deity of goblins. Other gods worshipped by the goblins include Khurgorbaeyag, the god of slavery, oppression, and morale, and Bargrivyek, the god of co-operation and territory.” Goblins have ‘an affinity for slavery’, though it is noted by players that many Dungeon Masters and players attempt to comb out features of the game that they find to be morally reprehensible.

While not explicitly linked; this last part is often noted as a red flag in DnD discussions. The notion that Jews worship at the altar of slavery is a well-known antisemitic canard. Ex-grand wizard of the KKK, David Duke, publicizes fictional scholarship attempting to create a false paper trail claiming that it was solely Jews who created, sustained, and profited from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. One may therefore choose to change the game in order not to include goblins worshiping a deity of slavery.

Cornish Tommyknockers

Tommyknockers, abbreviated to Knockers, are a part of Cornish folklore that eventually made its way to the United States. While identified by many folklorists under the label of goblin, others may label Knockers differently--however, their depiction frequently allows for them to set beneath the label. Furthermore, they appear to be the only goblins whose origin story explicitly links them to Jews in the imagination of the culture of origin.

“They are the ghosts, the miners hold, of the old Jews, sir, that crucified our Lord, and were sent for slaves by the Roman emperors to work the mines, and we find their old smelting-houses, which we call Jews' houses and their blocks of tin, at the bottom of the great bogs, which we call Jews' tin... (n.d.:255; Notes 1853:”¹⁶

In his article for the Western Folklore Academic Journal, James expands further on Cornish legend regarding Jews and Knockers: “In keeping with the idea that Knockers were spirits of Jewish miners, the Cornish maintained that the creatures did not work on Saturdays, which was their Sabbath. Contrary to this belief, however, the Cornish also maintained that the Knockers did not work on Easter, All Saint's Day, and Christmas, at which time they sang carols and held a Christmas mass deep within the mines. In addition, several authors suggest that Jews were associated with old mining works in Cornwall: "Jews' bowels" meaning small pieces of smelted tin in old smelting works; "Jews' houses," archaic smelting works; "Jews' leavings," mine refuse; and, "Jews' pieces," ancient blocks of tin. There is little variation in the traditions surrounding the Jewish origin of the Knockers, which seems to be the predominant folk explanation....The fact that the belief in a Jewish origin of the Knockers found its way into the fiction of Kingsley as early as 1851 underscores the importance of this tradition....Local tradition maintains that Jews worked in Cornish mines during the Middle Ages, but there is little historical basis for this belief Bottrell, Hunt, Evans-Wentz and Wright all suggest that the prominent folk belief was that Jews were exiled to the mines for the part they presumably played in the Crucifixion.”¹⁶

While he continues to discuss Knockers further, it doesn’t initially seem that antisemitic beliefs regarding the Crucifixion made their way into the American iterations of the Knockers (the idea of eternal suffering, labor, etc, for the crime of killing Jesus is not new).

The imagery associated with Tommyknockers in the modern era and historically is also quite distinctive. Many images that appear when one searches for Tommyknockers were actually created for other creatures but share many of the traits found above:

¹⁹, ²⁰, ²¹

Harry Potter

The most popular modern iteration of goblins comes from the Harry Potter series, written by a well-known bigot and transphobe, and expanded her bigotry further in the films and media. It is largely due to the franchises that conversations around goblins and Jews have gained any traction at all. Goblins in this franchise combine centuries of wide-ranging antisemitic tropes and stereotypes into a neat package: long, spindly fingers and toes, hooked beak-like noses, an affinity for blood and violence, believing their race to be above other races, forging silver and precious stones, having secret magic they refuse to share, speaking in a private language very difficult for outsiders to learn, and, of course, running the one bank which controls finances for the entire wizard world, which suggests that goblins have sole control of the fictional economy.

Goblins were introduced in the first Harry Potter book, but their lore has unfortunately continued to evolve. The Harry Potter Wikipedia, while not an official source for the franchise, includes this at the bottom of their page on goblins, ‘The goblin is an evil, mischievous creature from European mythology. Though they are described inconsistently in the myths of different countries, common traits include short stature, the magical ability of some form, and a love of money. The Goblins being good metalsmiths seems to be based on the dwarves of Nordic mythology”.⁷

The citation provided links to Wikipedia’s page on goblins, which has not a single mention of money or greed, despite the claim that goblins have ‘commonly’ been associated with money. This is a common argument in the case of goblins and Harry Potter; for surely if it has always been the case that goblins were greedy, money-hungry creatures, then their depiction in this particular form of media would be without consequence. But there is simply no evidence to substantiate this claim. And more importantly, if there were, it would not be enough to make a strong argument that the duration of a belief reduces its harm.It is virtually impossible to find direct mythological evidence of goblins as moneylenders, bankers, or involved with the economy in any organized manner. The only potential evidence of goblins' involvement in money includes their role as individual salespeople, giving gifts of money or jewels, or punishing the greedy.

Harry Potter’s goblins diverge dramatically from goblins of the past, just as the vampires of Twilight would be inconceivable for someone from before the time of Dracula or The Vampyre.

Goblins are introduced in book one during the first trip to the wizarding world, wherein Hagrid answers Harry’s question about wizarding banks, wherein he is immediately taught to fear goblins.

“Wizards have banks?”

“Just the one. Gringotts. Run by goblins.”

Harry dropped the bit of sausage he was holding.

“Goblins?”

“Yeah-so ye’d be mad ter try an’ rob it, I’ll tell yeh that. Never mess with goblins, Harry.”

The first physical description of goblins comes later in the chapter, wherein the goblin bank greeter is described as “about a head shorter than Harry. He had a swarthy, clever face, a pointed beard and, Harry noticed, very long fingers and feet. He bowed as they walked inside”. Here, the goblin bows to Harry and Hagrid, representing the subservient place goblins serve in wizard society. In the first film, Hagrid refers to goblins as “beasts,” though the official classification would be of being, not beasts.

The goblins not only control the currency, but the bank itself, as well as its security. The first book begins to amplify the idea that goblins are cruel and twisted.

“Stand back,” said Griphook importantly. He stroked the door gently with one of his long fingers and it simply melted away.

“If anyone but a Gringotts goblin tried that, they’d be sucked through the door and trapped in there,” said Griphook.

“How often do you check to see if anyone’s inside?” Harry asked.

“About once every ten years,” said Griphook with a rather nasty smile.

In the third book, we learn more of the uprisings of the goblins,

“But Hogsmeade’s a very interesting place, isn’t it?’ Hermione pressed on eagerly. ‘In Sites of Historical Sorcery it says the inn was the headquarters for the 1612 goblin rebellion, and the Shrieking Shack’s supposed to be the most severely haunted building in Britain –’”

The dates here are interesting as pointed out by keen-eyed readers, as the year 1612 aligns with the beginning of the Fettmilch uprising, which led to the temporary expulsion of Jews.⁸

After multiple characters display disgust towards goblins throughout the franchise, a character who worked alongside the goblins in the bank attempts to "both sides" the oppressive history between humans and goblins—despite the unmistakable power dynamic that places wizards above goblins.

"We are talking about a different breed of being. Dealings between wizards and goblins have been fraught for centuries ... There has been fault on both sides, I would never claim that wizards have been innocent. However, there is a belief among some goblins, and those at Gringotts are perhaps most prone to it, that wizards cannot be trusted in matters of gold and treasure, that they have no respect for goblin ownership."

There are a few ‘coincidences’ that further cement antisemitic tropes and caricatures into place. While not in the books or supposedly consciously chosen, the film location for Gringotts Bank features a Star of David on its floor. While the hexagram has existed outside of Judaism, it is an unmistakable symbol of Judaism and the Jewish people. It is vital to note that while the author of the texts wrote the goblins originally, the caricatures created by the films created a loop wherein they could feed off each other. The book did not describe long noses, but centuries of stereotype-informed decisions to give these creatures long noses. When asked about it, a Jewish organization stated, “the portrayal of the goblins in the Harry Potter series is of a piece with their portrayal in Western literature as a whole and is a testament more to centuries of Christendom's antisemitism than it is to malice by contemporary artists.”¹³

If they intended this to be a defense, it is a poor one: latent antisemitism that thrums in the veins of a Christian society and is imbued into books by a Christian woman, fleshed out by predominantly Christian artists, does not magically make it anything but antisemitism, as ordinary and mundane as Christian antisemitism is. The author's Christianity is well documented, as is her intention to write Harry Potter as an iteration of Jesus (the chosen one, death and resurrection to save all, etc.).

In 2023, a new Harry Potter game was released featuring a plot line hinging on goblins. The storyline expressly includes a goblin rebellion, led by a goblin, Ranrok, who is attempting to steal an ancient magic that is being kept in numerous (goblin-made) repositories after being ‘extracted’ by the “Keepers” (wizards and witches able to sense this ancient magic). The main characters attempt to stop Ranrok from harnessing this energy to free goblins (and other creatures) from being subservient to wizards. Despite their efforts, he absorbs the magic turning into a dragon. However, he is defeated in the end.

In the new game, goblins use “war horns,” which resemble Jewish shofars: ritual instruments. The game writes, “Horns like this were used by goblins during the 1612 Goblin Rebellion to rally troops and generally annoy witches and wizards. This horn was discovered in the aftermath of the rebellion behind the Hog’s Head Inn, with a wedge of gorgonzola stuffed inside--presumably to mute it”.

Jewish commentators have once again pointed out that the ‘coincidence’ of this horn being found in a “Hog’s Head” (fictional pub named after a famously unkosher animal), stuffed with gorgonzola (a famously historically unkosher cheese) linked to the year of an extremely well-known uprising of Jews seems to be altogether too improbable; especially considering the lead developer for quite a time, who only ‘stepped away’ late into the project proudly ran a conservative, reactionary YouTube channel, promoting things like GamerGate and cultural appropriation, which Warner Bros was supposedly aware of at the time of hiring him.

Did the author of Harry Potter and those involved in turning her words into media have antisemitic intentions? Frankly, this is not relevant to the question at hand, which asks whether or not the resulting impact of said creature is antisemitism, which, in the opinion of this article, is yes.

The goblins of the Harry Potter universe are without question antisemitic--whether or not that was the intention at the time of their creation (though one can even argue that they have not one creation story, but rather an ever-evolving one, with many hands involved in it). The common phrase, “impact over intent” is apropos: many can testify that intent does not assuage the harm of impact.

Antisemitism is at a crucial point: Jews are being shot in the street by people who believe Jews to be ‘primitive,’ controlling of the world and banks--whether or not you intend for your something to be antisemitic, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is, indeed, a duck.

The following screenshots are examples provided via a Tumblr user providing commentary on the game a well as goblin being used as a pejorative for Jews.

The Harry Potter goblins, which like Tolkien’s goblins before them, have undoubtedly inspired waves of goblins, and feature a new and unique manner of antisemitism relating to goblin archetypes. Goblins have not always been this way; yes, many contained antisemitic tropes by way of being created and existing in the mire of Europe’s medieval antisemitism. But they did not always control the banks while thirsting for raw meat and lumps of root vegetables; seeking to steal an ancient magic that will allow one to turn into a dragon [the lizard people conspiracy theory is also based in antisemitism and Jews have been accused of shapeshifting for centuries].

Twitter user pointed out the similarity between the Goblin Head award and an antisemitic propaganda film.

Why does this even matter?

As you have read this article, you have been forced to confront horrifying antisemitic propaganda from the last centuries which displays Jews as subhuman. But this is nothing more than a drop in the ocean of antisemitism. The belief that Jews have historically been the literal incarnation of evil is ancient and pervasive and while you may think that you would never fall for antisemitism so blatant as to portray Jews as inhuman goblins, your hubris may be your downfall. Having made it this far is a testament to your willingness to not allow hubris to let you fall into the clutches of bigotry, but to rather allow empathy and education be the wings that carry you to solidarity.

Seeing Jews as inhuman is not new. While you may think it is preposterous to see a goblin in a video game and link it to Jews, remember that bigots are far more numerous than you might want to believe and they do make these connections with glee.

Is [Insert Goblin from Media] Harmful?

There is no hard and fast rule about goblins. We cannot simply rule that every single goblin is hardline antisemitic because we are using a modern umbrella term for an endless stream of creatures from around the globe; even though the origins of the term lies in Europe. But that doesn’t mean that the folklore surrounding goblins cannot be antisemitic, because it absolutely can and is, on an increasingly frequent basis. It would be ahistorical to discuss goblins and pretend that the people who nurtured their image, iconography, and characteristics didn't harbor a deep seeded hatred of Jews, seeing Jews as subhuman, evil, and strangely magically powerful.

Antisemitic tropes rely on lack of education to worm their way into the common mindset, becoming so common that when they are called out, it is the whistleblower who is preposterous, not the perpetrator of harm.

Use critical thinking and context when looking into the goblin you are trying to analyze and cross-reference. For example, a goblin embodying one trope but existing completely outside of that context may not fall into the space of antisemitism. Still, more often than not, when multiple tropes exist simultaneously, you will cross the border into antisemitism, even unintentionally.

Remember: antisemitism is not merely the intentional, conscious, aware hatred of Jews but also the perpetuation of harm against Jews through harmful tropes, stereotypes, and canards.

-

Does it embody harmful tropes about Jews? (examples: do they horde wealth? Are they extremely greedy? Do they drink children’s blood? Do they use blood to make bread/crackers? Etc)

-

Where are goblins positioned in the story/piece of media? Are they always evil? Are they a persecuted group?

-

What is greater mythology is the story based in? Are the goblins consistent with the historical goblins of said mythology, even if said goblins go by other names?

Jewish Goblins

There are goblins that appear within the Jewish tradition as well. Modern iterations like the iconic children’s book “Hershel and the Hannukah Goblins” written by Eric Kimmel and illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman, published in 1989, are a delight. It is a folk tale featuring the Jewish folk legend, based on a genuine person, Hershel of Ostropol, as he travels to a Jewish town that has had its synagogue taken over by goblins. These demonic forces make it so that the Jewish population cannot celebrate Channukah. The brave, cunning hero, Hershel, outwits each and every goblin, allowing them to once again live without fear of attacks by these goblins. In this reimagination of the Channukah story, antisemitism and persecution is put into goblin form, turning the imagery of goblins on its head. A Jewish picture book published in 2017, The Goblins of Knottingham: a History of Challah, written by Rabbi Zoe Klein, features “a group of children band together to defeat the goblins is an original and unique "history" of challah”.¹²

Jewish folklorists also infrequently used the term to describe creatures found within the Jewish tradition, though the term seemingly did not pick up steam within the Jewish community as it did outside of it, with the most prolific modern compendiums of Jewish magical history omitting it from their indexes entirely.

With gratitude to the perspectives of A Hearth Witch (German-American folklorist and witch, whose Patreon provides in-depth writings on the topic).

Sources:

-

Martin, L. (2006) The Jew in the thornbush: German fairy tales and antisemitism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: Musaus, Naubert and the Grimms'. Modern Language Review . pp. 123-141. ISSN 0026-7937

-

Big-City Jews: Setting and Censoring the Modern Fairy Tale Book Title: Drawing the Iron Curtain Book Subtitle: Jews and the Golden Age of Soviet Animation Book Author(s): MAYA BALAKIRSKY KATZ Published by: Rutgers University Press

-

Arieti, James A. “Magical Thinking in Medieval Anti-Semitism: Usury and the Blood Libel.” Mediterranean Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 2016, pp. 193–218. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/mediterraneanstu.24.2.0193. Accessed 11 Dec. 2022.

-

Goblin Mythology: A Brief Study of the Archetype, Tracing the Explications in English Literature By Annliya Shaijan University of Calicut

-

https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1172&context=mythlore

-

Goblins Author(s): W. A. Senior Source: Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts , 2002, Vol. 13, No. 2 (50) (2002), pp. 110- 113 Published by: International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts

-

"Dwarves Are Not Heroes": Antisemitism and the Dwarves in J.R.R. Tolkien's Writing Author(s): Rebecca Brackmann Source: Mythlore , Spring/Summer 2010, Vol. 28, No. 3/4 (109/110) (Spring/Summer 2010), pp. 85-106 Published by: Mythopoeic Society

-

https://www.amazon.com/Goblins-Knottingham-History-Challah/dp/1681155265

-

James, Ronald M. “Knockers, Knackers, and Ghosts: Immigrant Folklore in the Western Mines.” Western Folklore, vol. 51, no. 2, 1992, pp. 153–77. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1499362. Accessed 11 Dec. 2022.

-

The Ghost Hunt Uk states this is an ancient depiction of Tommyknockers https://theghosthuntuk.com/tommyknocker-legend-of-the-mines/

-

Nevada Magazine 1965, via https://steemit.com/history/@itsallfolklore/knockers-ghosts-and-tommyknockers

-

Graphic by Rob Rath https://www.distinctlymontana.com/do-tommyknockers-lurk-darkness